It’s 1980. The decade of the 70’s has come to an end, and with it, a time when space travel seemed to be achievable in the near future. Fueled by Apolo’s XI landing in 1969, science fiction had just experienced a sudden rise that had even been promoted to the mainstream media (Star Trek, Star Wars, The Andromeda strain…), opening questions about space travel and extraterrestrial life.

It is in this context that the famous series Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, one of the most influential pieces of popular science, airs. Throughout the series, the astronomer, astrophysicist and science writer Carl Sagan, marvels the audience with explanations about life and the universe.

In one of the episodes, deeply influenced by the events of that decade, the scientist asks a bold question: What would life on Jupiter be like? This is, of course, an outlandish question which some scientists would surely consider somewhat farfetched. What not so many people know, though, is that this was not a mere resource to draw the attention of the public. In fact, it was part of a scientific exercise published by Sagan and Edwin E. Salpeter, an astrophysicist from Cornell, in 1976.

The paper, entitled Particles, environments, and possible ecologies in the Jovian atmosphere presents a series of scientific imaginary creatures and theoretical inhabitants of Jupiter.

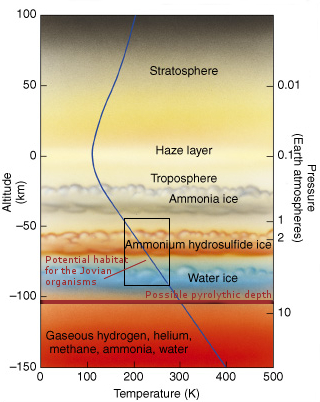

The main question regarding life on Jupiter is how to survive on a planet made out of mainly gas (we would not recommend living in the extremely pressured nucleus).

The answer is simple: the Jovian fauna would consist of floating organisms that would survive in the inhabitable layers of the atmosphere. Sagan draws a parallelism between this theoretical ecosystem and the marine planktonic communities. In this type of community, the primary producers (mainly algae and bacteria) remain in the sunny layers of the water column. Through decay or transport via marine currents, these organisms (or their remains) end up in the lower parts of the water column, feeding the remaining trophic chain.

The Jupiter ecosystem would function similarly but with different actors. The actors of this Jovian ecosystem are as follows:

Sinkers

Sinkers would be small organisms unable to remain stable in the upper parts of the atmosphere, slowly sinking to the centre of the planet or following the planet’s wind currents.

Their lifestyle would be similar to that of bacteria or some protozoa: they have fast life cycles and the ability to cope with harsh environments, either through specializations in the membrane… or by a form of cryptobiosis.

And what would they feed on? One option is that these organisms would be photosynthetic, absorbing the light of a distant Sun using their light-harnessing chromatophores. The second option would be for them to be heterotrophs, capturing organic molecules present in the atmosphere (according to the authors, some molecules, like ethane, could be present as a photoproduct of Jupiter’s methane).

Floaters

Floaters are, floating organisms. But floating on a gas planet is difficult: the atmosphere of Jupiter is already full of hydrogen and helium, and these organisms would need a different, lighter gas to float. Instead, they would probably heat up with their internal metabolism.

Sagan and Salpeter calculate that the floaters would reach sizes of kilometers, and that the future spacecraft reaching Jupiter, like the Mariner, would be able to detect them from afar. Basically, they would be city-sized balloons.

Floaters would be photosynthetic, using either methane or ammonia as their source of energy (electron donors). The alternative would be, once again, for them to absorb organic molecules via passive diffusion. Although the sight of such organisms would certainly be jaw-dropping, Sagan and Salpeters also point out that with known cell structures, these organisms would be as stable as a bubble, and would easily burst.

Hunters

Hunters are the fishes of this system, consumers that float thanks to specialized structures and surf through the Jovian atmosphere preying on the unfortunate sinkers. Their body size would also be gigantic, like the floaters.

Scavengers

Scavengers are the type of fauna that we would find in the depths of the marine ecosystem which would feed on dead organisms or residues of organic matter. Scavengers would behave in a similar way to Floaters, but would certainly not be photosynthetic and rather eat on anything, like pieces of floaters or dead sinkers.

Life on Jupiter

But Jupiter is not exactly a mild environment, temperatures can reach up to 600ºC, pressures up to 106 Pa, winds about 100 m/s and the atmosphere is struck by huge thunderstorms. Actually, it is difficult to think about any organic molecule surviving under those conditions.

In fact, life on Jupiter is currently thought to be almost impossible. Sagan and Salpeter thought that life could be still present in a very small section of the planet. Everywhere else, organic structures would be destroyed, especially at the lower levels of the atmospheric column. If organisms would fall, they would encounter a “pyrolytic depth”.

Falling to the pyrolytic depth would be a huge selective pressure for the inhabitants of Jupiter. Floaters, scavengers, hunters and especially sinkers would need to complete their life cycles before falling into these layers.

One important part of this life cycle involves, of course, reproduction. The authors propose a type of reproduction involving “dispersules”, in which the animals would divide themselves into small pieces able to create new organisms. Interestingly, the authors also propose that hunting would work similarly, where Hunters making “the distinction between hunting and mating under these conditions (is) not sharp”.

Particles, environments, and possible ecologies in the Jovian atmosphere is mainly an astrophysical paper, though, and not much more detail is explained about the ecology or biology of these organisms (there is though, much more to read about atmosphere composition and structure, photoproduction…).

So, what does this entry of The scientific imaginary creatures tell us? It is clear that such organisms do not exist, but this exercise does something that is indeed remarkable: it ties up completely different disciplines and creates a scenario where imagination and the limits of biological life are put to the test.

Adolf Schaller was responsible for portraying these imaginary animals in Cosmos: A Personal Voyage. You can find the story of this process here. The images for this article are personal drawings (yes, I still have more to learn) based on Schaller’s portrayals (with the exception of the Scavengers, a personal creation).

Bibliography

Sagan, C., & Salpeter, E. E. (1976). Particles, environments, and possible ecologies in the Jovian atmosphere. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series, 32, 737-755.

If you liked this article and want to support us, follow us on twitter and facebook !