Animal diversity is stunning. Our planet is full of wonders beyond our imagination: animals that survive in the harshest of conditions, parasites that have become ultra-specialized, animals that use the sun for energy… the list has no end.

We hardly ever wonder about the incredible diversity of creatures that live between us.

It is in this diversity, that we often find animals completely different to anything else.

What are the main animal groups, or phyla?

Scientists classify animals into 34-36 (more or less) groups, each containing hundreds of thousands of species. These groups, called “phyla” include, for example, the arthropods (spiders, crabs, insects…), the cnidarians (jellyfishes) or the echinoderms (sea urchins, sea stars), to name a few. Each of these groups has a series of characteristics that are clearly different from the other groups.

To give an analogy, imagine a box full of tools. You may have different-sized screwdrivers, tweezers with different shapes… Each of these would represent an animal species.

Even with this diversity of tools, you could easily classify them: as smashing tools, cutting tools… And you probably base this classification on some property. For example, screwdrivers may be made of the same material as a hammer, but they are characterized by their handle and thin tip.

For example, the phylum of the chordates has all animals that have (or had) a backbone, slits on their pharynx and a tail, among others. This group encompasses animals like fish, birds, or us. Some of these features may have been lost throughout evolution (in our case, the tail), but we all chordates had them at the very beginning.

Most phyla have hundreds to hundreds of thousands of species, but there are some phyla with just one or two species. These animals are so different to anything else, that scientists had to create entire categories just for a couple of species-

These animals have been puzzling scientists for decades and some continue to do so. At OnElephantsandBacteria, we call these groups the microphyla.

The series of post: Strangers in the Animal Tree, covers these rare animals.

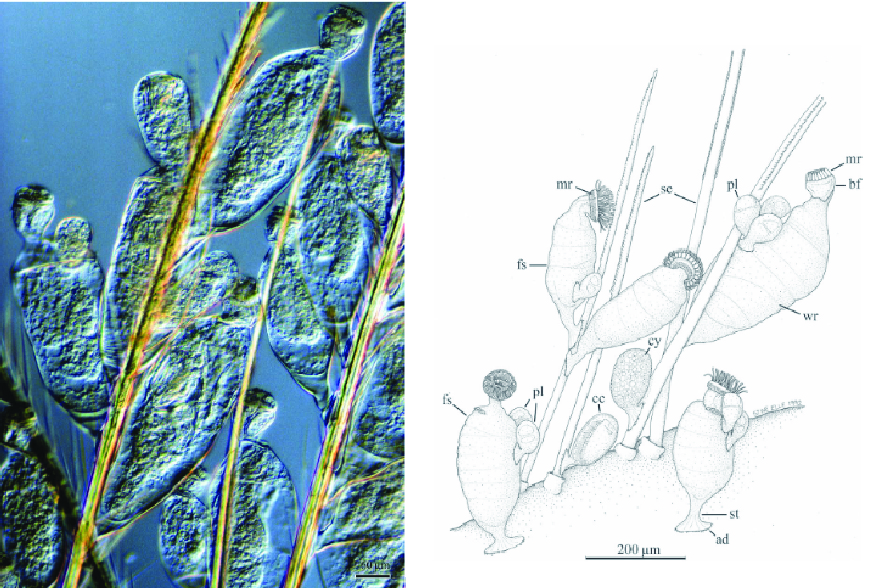

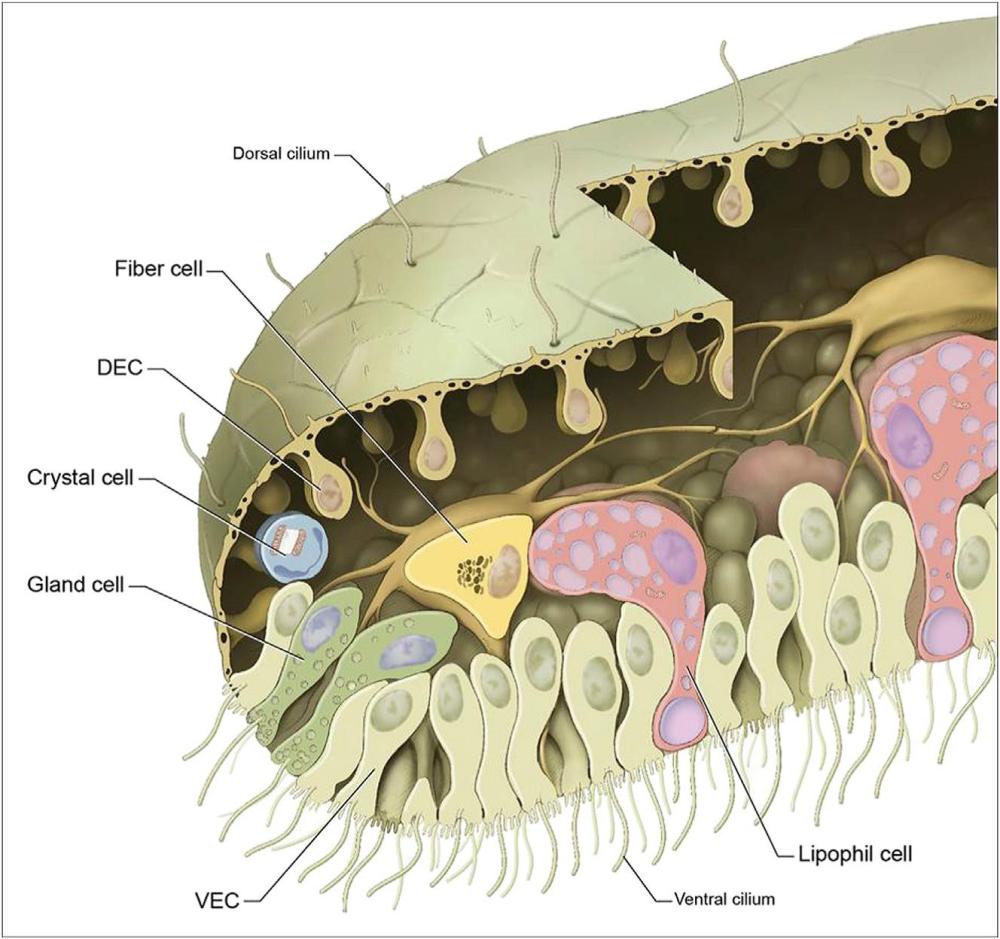

Cycliophora: the animals that live in the mouths of lobsters

Cycliophora literally means carriers of small wheels, a fitting definition.

Symbion pandora and Symbion americana, the only described species for this phylum, are 1mm-sized organisms that were originally found attached to the mouth of Norway’s lobster Nephrops norvegicus. Since then, cycliophorans have appeared attached to the common lobster, which inhabits the coasts of Europe (and is commonplace in fish markets and restaurants) and to the Homarus americanus, the American lobster, and their larvae have similarly been identified.

But what does “small wheels” mean?

The mouth of cycliophorans is a trumpet-like structure that they use to filter food particles from water. Unique to cycliophorans is the fact that these “trumpets” grow first inside the body and protrude later. If one is damaged, another one starts to grow inside as a replacement.

As other marine animals, the life cycle of cycliophorans is overcomplicated (just to name a few examples: the colonial Thaliacea or the parasitic cycles of some Plathyelminthes go through an incredible number of life stages with different anatomies and functions).

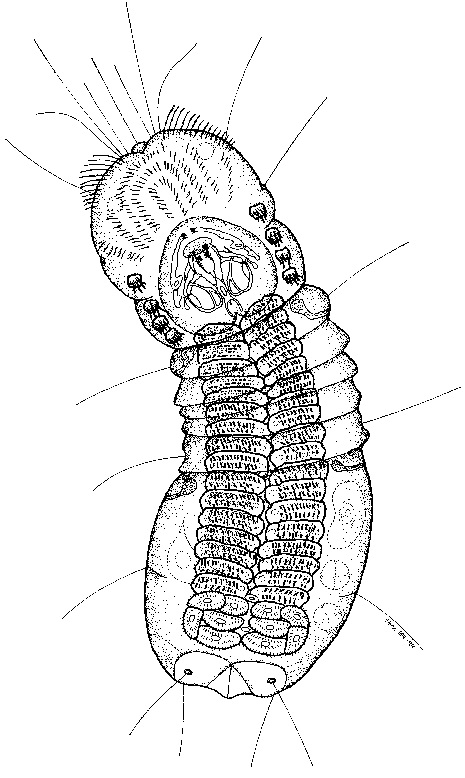

In fact, cycliophorans can only eat in one life-stage: once they are attached to the shrimp’s mouth. For the majority of their life, cycliophorans are just fast-reproducing organs. Even males are reduced to their minimal expression; their entire digestive system is reduced, and their sole purpose seems to be reproduction. The larvae of cycliophorans grow inside their body and are released afterwards. These larvae, conveniently named Pandora roam freely until they find a new shrimp, they attach themselves and proceed to adulthood.

This is the simplified version, the reproduction of cycliophorans is even more chaotic:

Although the reproductive cycle is not completely known, everything points to one complex system (that I’ll try to summarize in one sentence): one feeder can produce either a female or male stage inside, males escape and attach to feeders with growing females inside, then females escape and attach with sticky cilia to the mouth of the lobster, meanwhile the male produces two secondary males inside its body that fertilize the female, afterwards inside the female a new larvae (choroid) grows, eventually bursts its way out of the female and escapes and finally it attaches to the lobster (again), which gives a new son feeding stage (you are allowed to breathe, now).

To sum up, Ciclyophorans are still quite enigmatic, although its position in the animal tree of life seems to be quite clear (sisters to Entoproctans, also a rather obscure clade of tiny marine animals). As a moral of the story, never underestimate your neighbor lobsters.

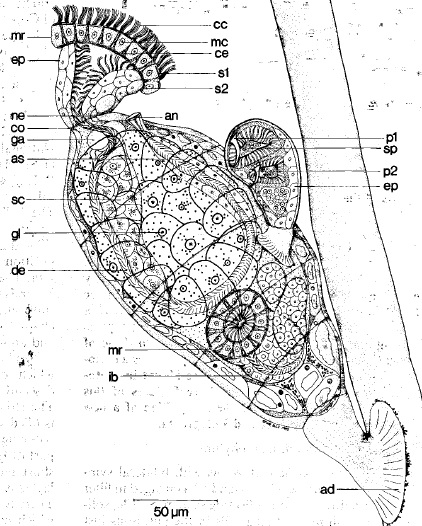

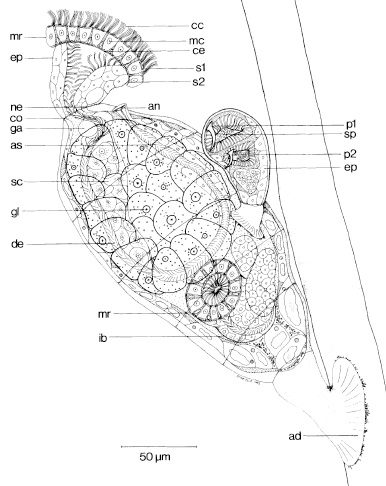

Micrognathozoa, one of the most complex mouth on Earth

Continuing with mouth issues, now we confront Micrognathozoa, with Limnognathia maerski as the only representative. This animal was discovered in an island near Greenland (Disko Island) during a university field trip, back in 1994, and also has been also found in Crozet Islands (Anctartica), so the completely opposite part of the world. Limnognathia maerski wasn’t formally described until 2000, although for the first moment was placed as a unique pyllum in the Gnathifera, a clade that gathers a plethora of strange microscopic phyla. It is believed that these animals could be relicts from the Cretaceous, when their actual habitat was a tropical reef.

Limnognathia maerski usually lives swimming on the surface of mosses, where it hunts algae and bacteria. Despite this basic diet, one of the most prominent features of this animal is its mouth (take a look at the first image in the post!). It’s composed of almost 15 pieces that measure about 14 µm and are united by muscles, working in a similar way as Arthropod and Vertebrate jaws. Interestingly it doesn’t have a fully functional anus (just temporarily functional) and usually protrudes the jaws, in a kind of “vomit” behavior in order to expel its residues.

Concerning the reproductive cycle… well, only female specimens have been found so far (should I change all the “its” for “she”, then?) and it is believed to reproduce by parthenogenesis, as many other freshwater animals of the meiofauna.

Thanks for reading!

Bibliography

Kristensen, R. M. (2002). An introduction to Loricifera, Cycliophora, and Micrognathozoa.Integrative and Comparative Biology, 42(3), 641-651.

Sorensen, M. V., Funch, P., Willerslev, E., Hansen, A. J., & Olesen, J. (2000). On the phylogeny of the Metazoa in the light of Cycliophora and Micrognathozoa. Zoologischer Anzeiger, 239(3-4), 297-318.

Obst, M., Funch, P., & Kristensen, R. M. (2006). A new species of Cycliophora from the mouthparts of the American lobster, Homarus americanus (Nephropidae, Decapoda). Organisms Diversity & Evolution, 6(2), 83-97.

Funch, P., & Krlstensen, R. M. (1995). Cycliophora” is a new phylum with affinities to I. Nature, 378, 14.

Giribet, G., Sørensen, M. V., Funch, P., Kristensen, R. M., & Sterrer, W. (2004). Investigations into the phylogenetic position of Micrognathozoa using four molecular loci. Cladistics, 20(1), 1-13.

Brusca, R. C., & Brusca, G. J. (2003). Invertebrates. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates.

3 Comments Add yours